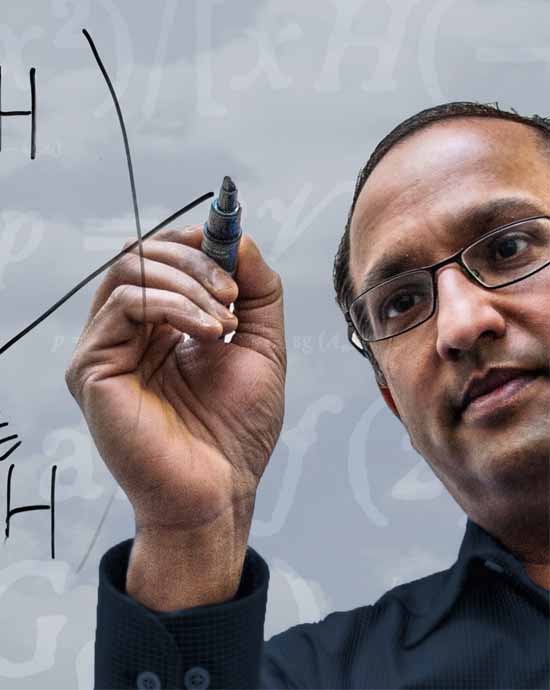

VINTAGE TOP MATERIALS

Details of Components

Cloth Weave Construction

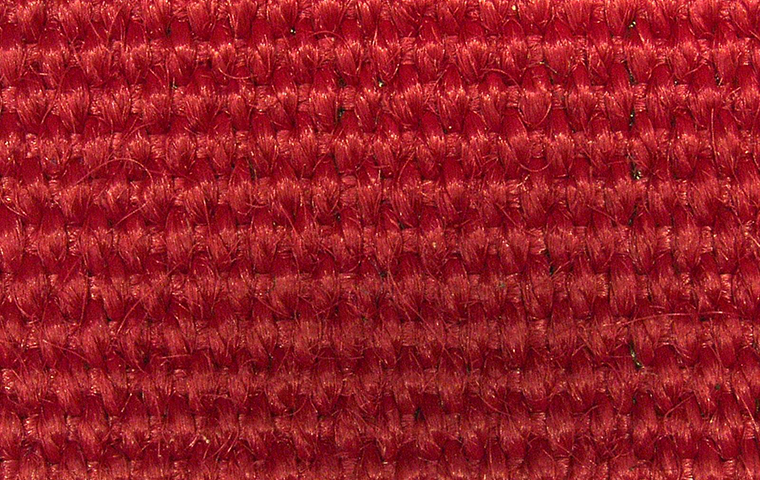

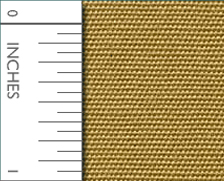

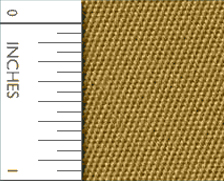

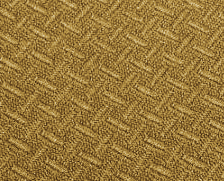

Because the various top materials use different kinds of cloth, a few of the more common weave types are worth defining. Duck, or Square Weave, dominated as face fabric on cloth top materials for many years. The weave is a simple alternation of yarns going over one intersecting yarn and under the next (Figure 4). Twill Weave, a favorite as a cloth top face fabric since the 1980s, has a weave that gives a strong diagonal pattern (Figure 5). The diagonal lines normally run “up” toward the right edge of the cloth. The twill weave limits top material stretch, which is advantageous for dimensional stability at high driving speed. Drill Weave cloth, usually used for the lining or backing of top material, has a diagonal pattern that is usually finer than a twill weave, the diagonals usually running “up” toward the left edge of the fabric. For many decades the premier grades of European cloth topping used a Dobby Weave lining (Figure 6), this being the criss-cross pattern well known on the lining of Mercedes-Benz top material.

|

Square Weave

|

Twill Weave

|

Dobby Weave

|

Cloth Fiber Composition

Throughout the first century of automobile production, most top material cloth consisted of cotton fibers, both on the facing and lining. Prior to 1917 the auto industry used substantial quantities of mohair facing fabric on the cloth toppings. Wool, generally blended with cotton, saw at least a fair amount of use prior to the mid-teens, sometimes being passed off by less scrupulous sellers as premium-grade mohair. From the mid-teens through the late 1930s, few automobile top materials utilized anything other than cotton fabrics. A little mohair was used for specialized premium materials in North America. The United Kingdom’s auto industry apparently used mohair more extensively, into the 1950s. Rayon and other synthetic fibers became accepted for interior automotive trim, but could not withstand the much harsher exterior applications until the very late 1930s.

In the late 1940s, coated fabric producers began to offer top materials incorporating synthetic-fiber cloth, either as a blend with cotton, or totally of synthetic fiber. As applied to production top materials, blends of Rayon and Cotton achieved fairly wide use for facing fabric on rubber-coated cloth topping from the late forties through the mid-fifties. Car stylists liked the Rayon because its solution-dyed fibers had colorfastness superior to that of dyed cotton fiber. However, the Rayon was susceptible to heat shrinkage and degradation from acidic rain, particularly in industrialized regions. Orlon, a DuPont acrylic fiber, was used for cloth topping face fabric from the early 1950s through 1957. In the more recent generations of top materials, acrylic has gained dominance for facing fabrics. Linings of top materials have used cottons, polyester and cotton blends and even all-polyester in limited instances. Despite a persistent public misconception, nylon has never been used in any production automobile top material, at least in North America.

Cloth Coloration

Textile coloration varied with style trends and technology. The performance demands of automotive textiles have, at times, forced advances in the production and dying of cloth. With the harsh exposure to ultraviolet light and to general weathering, the demands for colorfastness usually challenged the textile makers. Black, tans and earth tone colors traditionally offered the best fastness (colorfastness) for dyed natural fibers. Brightness of the colors improved over time. By today’s standards, exterior fabric colors from before 1940 look dull and drab, but were very acceptable in their day.

Usually, a uniform, monochromatic cloth was dyed after weaving, or piece-dyed according to industry terminology. Color variations could be imparted in a cloth by weaving together different colored yarns, these being referred to as yarn-dyed fabrics. Commonly these involved two or three different yarn colors, but a few exotic offerings in the twenties and thirties consisted of four different colors. Blending of fiber colors in yarn production was (and still is) another technique for achieving a multi-colored effect. Of course this kind of cloth would be referred to as a fiber-blend.

When synthetic fibers came into strong use around 1950, colorfastness was improved by the use of solution dyed fibers. These were produced from a plastic melt stock in which the color was integral, yielding a fiber with color throughout. Dyed fibers receive the color pigmentation only at or near their surfaces. Known in the trade as “Double Texture”, this construction has traditionally been the longest lasting and most robust surface-coated top material. Some users have noted that double texture’s extra layers of cloth and rubber impart better sound deadening (for convertibles) than single texture material and modern acoustical tests on soft tops confirm this point.

Coating Compounds

Coating substances also evolved greatly over the first century of automobile production. Early in the twentieth century one could choose between natural rubber and pyroxylin. The latter was a cellulose nitrate material used for many kinds of coated fabrics, including some top materials, upholstery and trim fabrics. Pyroxylin was typically used as a surface coating, particularly where a color other than black was wanted. Rubber saw use for the combining film in cloth toppings, and for surface coatings on single and double texture materials. In the 1950s synthetic rubbers and vinyl replaced the earlier choices. As a surface coating, vinyl achieved particular favor because it provided great functionality, a wide variety of color choices and relatively low cost compared with other compounds.